Where Economic Empowerment and Social Equity Collides with Host Community Approvals

Adult-use marijuana legalization in 2016 brought hope to many advocates, consumers and businesses. The opening of the first two adult-use recreational shops in November 2018 was a euphoric moment for consumers willing to brave long lines in the cold to be the first to legally purchase cannabis. The 26 adult-use stores owners are delighted as their cash registers ring nearly non-stop. But for the other 191 prospective store owners, opening an adult-use marijuana store in Massachusetts is an excruciatingly slow, overly expensive, and generally painful experience.

The Massachusetts law that enabled adult-use marijuana – Chapter 94G – was designed to create an orderly and timely roll-out of the legalized cannabis industry. Unfortunately, the reality at ground level has been anything but that. The law requires the Cannabis Control Commission to either issue the appropriate license or send the applicant a notice of rejection [citing specific reasons why the commission did not approve] within 90 days from the date of submission of a completed application and associated fees. To date, there have been 218 retail marijuana establishments with finalized applications. One application was formally denied by the Commission. Of the remaining 217 applications, 26 made it across the proverbial finish line to open their stores; seven hold a final license, 44 have a provisional license, and 140 remain in the application review queue.

Under the licensing program, once a provisional license is granted, an applicant can complete the store build-out, install security systems, build storage, and train staff. When ready, the applicant requests an inspection to receive a final license. With that penultimate step of licensing in hand, the applicant acquires inventory, loads items into the Commission’s METRC tracking system, and requests permission to commence operations. Stores are generally allowed to open three days after the final authorization is granted.

A review of Commission reports for license applications in all categories that have submitted all the required packets[1], shows the process is not working as planned. The average time[2] from submitted application to provisional license is 122 days. To move from provisional to final license takes an average of 125 additional days. This is based on the 89 applicants who have made it to the final license stage. The other 339 applicants have been waiting in the submitted application queue for approximately 162 days each. While it may seem like a small price to pay to secure a coveted adult-use license, time is money. For many small businesses [especially economic empowerment and social equity applicants], these delays eat away at limited capital reserves, making it nearly impossible for them to compete with larger companies who have deep-pocketed investors.

Slow becomes slower

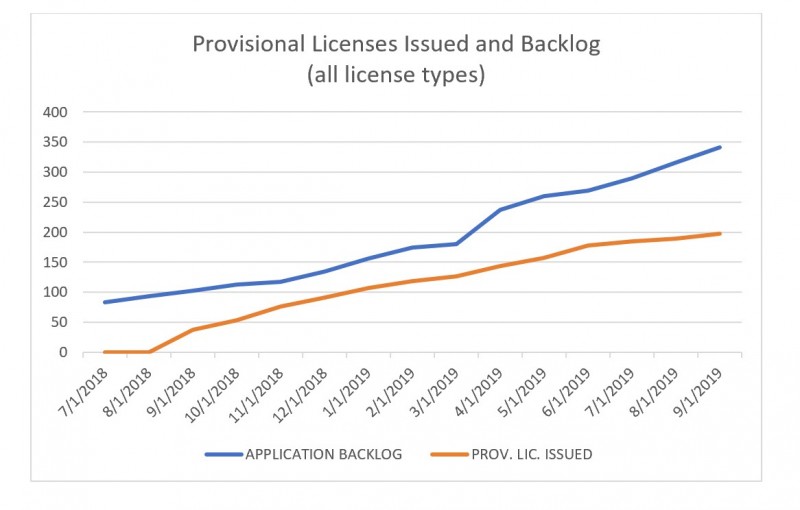

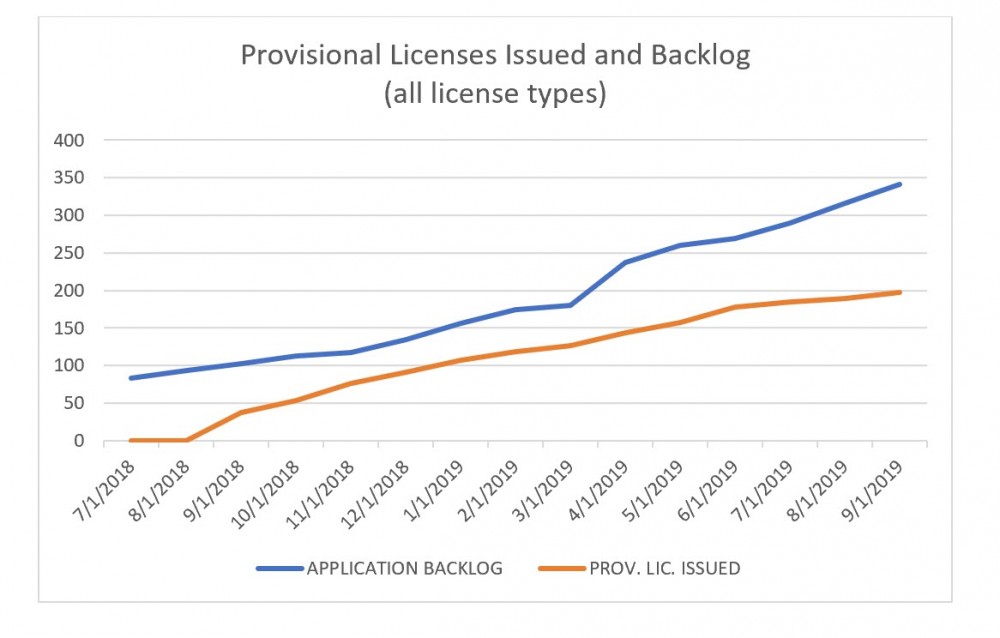

Over the past 12 months, the commission has issued nearly 16 provisional licenses per month. At that pace, it will take nearly 22 months to clear the existing backlog; and that doesn’t consider the applications that will be filed when communities like Boston, Springfield, Cambridge, Lowell, New Bedford, and Quincy issue Host Community Agreements [HCA] (see table at end of article). At the current pace, new applicants could be waiting up to 2 ½ years for their 90-day decision. As the table at the end of this article shows, the average amount of time to clear the backlog will only continue to grow.

Applicant’s nightmare is a landlord’s dream

So far, the 243 of MA’s 351 municipalities that allow marijuana establishments require that an applicant financially secure a retail location before appearing before the governing body (often City Council or Selectmen) to apply for a local HCA. Cities and towns are required to allow a minimum number of adult-use retail stores equal to 20% of the number of carry-out liquor licenses. Most communities have opted for the smallest number and have segregated operators into tightly zoned areas. Due to this cap, retail licenses are the highest in demand and the most difficult to get of all recreational cannabis business categories. The examples that follow demonstrate what is taking place across the state; a windfall for landlords while squashing the dreams of small business owners, Economic Empowerment and Social Equity applicants.

A MetroWest town had 48+ interested parties for two HCA slots and a handful of vacant store fronts within the marijuana retail zone. When the multitude of candidates descend upon a few select landlords, the ensuing bidding war results in an uncompetitive advantage going to the best capitalized teams. Due to the burdensome costs of securing real estate in advance, approximately 40 of the prospective applicants may never have an opportunity to appear before the town’s board to present why they provide the best option for the town. The landlords, in essence, are now determining the winners, not the municipality. This is a recurring theme throughout the Commonwealth.

In Maynard, an applicant recently executed a six-month lease to hold space in order to apply for an HCA. Less than two weeks later, when they appeared before the Select Board, they discovered that the proposed location was not favorable and would not be approved. It cost them $21,600 to learn that harsh lesson. In Framingham, a landlord, knowing that a location was a required element of the city’s application process, demanded a $10,000 fee to execute a letter of intent, even though the current tenant had not yet vacated the space and would not be out for months.

Ware selectmen granted their first retail HCA to local mother and daughter team, B Leaf Wellness Centre. Competition for the one remaining HCA heated up quickly with three candidates: a husband and wife team from New Hampshire, a local property owner, and a publicly-traded multi-state operator (MSO). The Board of Selectmen discussion was heated as the process turned into a virtual auction, with the MSO promising $15,000 to a charity of one selectperson’s choosing and agreeing to prepay $50,000 of the community impact fee as soon as their license was awarded. Since the other teams were unwilling to participate in the pay-to-play “donation” process, the MSO won the HCA.

Webster zoned adult-use retail stores to locate either in the industrial park or Webster Plaza, where most of the storefronts are empty/closing and space is offered at $14-17 per square foot. The broker informed potential marijuana retailers to bid “at least $25 a foot” to be considered. The town selected two operators and submitted both to the landlord to make the final selection. The runner-up turned to the Webster industrial park where space is advertised at $8.50 per foot. A landlord referred by the town was asking over $27 per foot [more than three times the going rate] and required a $15,000 non-refundable deposit. With several parties seeking that last coveted HCA, the landlord had no incentive to reduce their price and within days the property was leased. These incidents are commonplace and not limited to retailers. A large cultivation landlord has stated they expect to recover their development costs within 1 ½ years.

By requiring applicants to first secure and financially hold a location before applying for an HCA, municipalities are inadvertently lining the pockets of landlords. Paying rent or “hold fees” to landlords throughout the extended licensing process [combined with premium rental rates] creates the equivalent of an industrial vacuum cleaner: sucking capital away from smaller businesses, economic empowerment and social equity applicants while leaving them dry and creates an industry dominated by larger, deep-pocketed, and increasingly multistate, operators, far from the Commonwealth’s constituents that the law was written to help.

The Logjam Reverberates Forward

The slow roll-out is not only impacting aspiring retailers. The state's marijuana ecosystem relies upon multiple license classes to connect from seed to consumption: product manufacturers that infuse marijuana plant oils into baked goods, topical ointments, patches, sublingual tinctures and vaporizers; specialty transporters that move product securely between cultivators, testing laboratories, product manufacturers, retailers, and research facilities; independent testing laboratories to certify the safety of products; and soon, home delivery agents. With many of the earlier retailers under common ownership with fully integrated registered (medical) marijuana dispensaries, their supply chain is internal, allowing them to rely upon their own grow, processing/manufacturing, and delivery operations. In the world of retail marijuana, the opportunity for small business owners without deep pockets is extremely limited. A robust network of independent retailers is necessary to support a full ecosystem of marijuana entrepreneurs.

With few exceptions, the Commission reviews applications on a first-in, first-look basis. Therefore, with 218 retail applications submitted, 140 of them still under pre-license review, demand for intermediary services will be constrained into the foreseeable future. Without a robust independent retail store base, supply-chain businesses [many of whom are smaller local operators] will struggle to identify sufficient retailers to sell their products to, creating a void in their ability to achieve near-term profitability. Carrying operating losses on top of the losses incurred during the licensing phase can be more than many smaller firms can handle.

As social equity and economic empowerment candidates are forced to the sidelines, allowing them a fair shot at a business opportunity will require stripping control of local approval from the landlords and reducing the application processing time down to the 90-day legislative mandate. Otherwise, disadvantaged candidates will find themselves simply treading water or floating belly-up in red ink. Time is rapidly running out to successfully foster all the elements necessary to an inclusive fully functional cannabis business ecosystem.

(For those readers interested in numerical breakdowns, we include an addendum that analyzes certain application details. Warning: don’t read it, unless you’re into numbers.)

Addendum: By the Numbers

Application Activity, Provisional Licenses Issued, Backlog, and Months to Clear the Queue

|

Month |

Jul-‘18 |

Aug-’18 |

Sep-’18 |

Oct-’18 |

Nov-’18 |

Dec-’18 |

Jan-’19 |

Feb-’19 |

Mar-’19 |

Apr-’19 |

May-’19 |

Jun-’19 |

Jul-’19 |

Aug-’19 |

|

1. Apps In |

86 |

9 |

49 |

26 |

30 |

31 |

38 |

28 |

13 |

74 |

37 |

34 |

28 |

29 |

|

2. Less: |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

3. Net Apps |

86 |

8 |

49 |

26 |

30 |

31 |

38 |

27 |

13 |

73 |

37 |

30 |

26 |

28 |

|

4. Prov Lics |

- |

- |

38 |

15 |

23 |

15 |

16 |

11 |

8 |

18 |

13 |

21 |

7 |

4 |

|

5. Avg. PLs |

|

|

38.0 |

26.5 |

25.3 |

22.8 |

21.4 |

19.7 |

18.0 |

18.0 |

17.4 |

17.8 |

16.8 |

15.8 |

|

6. Backlog |

86 |

94 |

105 |

116 |

123 |

139 |

161 |

177 |

182 |

237 |

261 |

270 |

289 |

313 |

|

7. Mo to Clear |

|

|

2.8 |

4.4 |

4.9 |

6.1 |

7.5 |

9.0 |

10.1 |

13.2 |

15.0 |

15.2 |

17.2 |

19.9 |

- Completed applications where all packets have been submitted and the application fee paid

- Less: Denied applications and withdrawn or terminated applications. One denied application has since been issued a provisional license

- Net Applications represents new complete applications less those withdrawn, terminated, or denied

- Provisional licenses represents provisional licenses issued. The Commission controls issuance of provisional licenses. Because the applicant must perform various tasks to move from provisional to final license, timing for that stage is not within the Commission’s exclusive control

- Avg. Prov. Lic. Represents the average number of provisional licenses issued each month, starting with the first provisional licenses that appeared on the September 2018 report

- Backlog is the cumulative amount of submitted and complete applications awaiting a Commission decision for issuance of a provisional license

- Months to clear represents the number of months needed to clear the backlog, based upon average number of provisional licenses issued

Average license approval performance over prior three and six months:

|

|

Lifetime |

Mar - Aug |

Jun - Aug |

|

Applications Submitted |

512 |

215 |

91 |

|

Less Denied or Terminated: |

10 |

8 |

7 |

|

Net Applications |

502 |

207 |

84 |

|

Prov Licenses Issued |

189 |

71 |

32 |

|

Avg. Monthly Licenses Issued |

15.8 |

12 |

11 |

|

Application Backlog |

313 |

313 |

313 |

|

Months to Clear Backlog |

19.9 |

26.5 |

29.3 |

How far applications have advanced (Data set 9/13/2019):

|

License Class |

Apps Submitted |

Denied |

Provisional Licenses |

Final Licenses |

Commence Operations |

|

MARIJUANA RETAILER |

218 |

1 |

44 |

7 |

26 |

|

MARIJUANA PRODUCT MANU |

128 |

1 |

27 |

7 |

17 |

|

MARIJUANA CULTIVATOR |

161 |

[3]3 |

32 |

10 |

17 |

|

MARIJUANA MICROBUSINESS |

13 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

CRAFT MARIJUANA COOPERATIVE |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

EXISTING LICENSEE TRANSPORTER |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

THIRD-PARTY TRANSPORTER |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

MARIJUANA RESEARCH FACILITY |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

INDEPENDENT TESTING LAB |

6 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

UNDEFINED |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

TOTALS |

540 |

5 |

108 |

25 |

64 |

540 applications have been submitted. Five were denied, though one of those denials (a cultivator) did eventually secure a provisional license. 197 provisional licenses have been awarded. Hence, there are 339 remaining applications in the submitted application queue.

197 applicants have been awarded a provisional license. 89 of those licensees have been awarded a final license. Hence, there are 108 remaining provisional license holders.

89 applicants have been awarded a final license, 64 have received authority to commence operations. Hence, there are 25 remaining final license holders.

What’s waiting to come in (communities with at least 8 retail stores):

|

Municipality |

Off-Premise ABCC Licenses |

Min. MJ Stores (20%) |

Retail Apps Submitted Thru 9/13/2019 |

Likely Remaining Apps to be Filed |

|

Boston |

267 |

54 |

7 |

47 |

|

Worcester |

57 |

12 |

9 |

3 |

|

Springfield |

55 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

|

Lowell |

43 |

9 |

1 |

8 |

|

Fall River |

40 |

8 |

6 |

2 |

|

Lynn |

40 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

|

Brockton |

38 |

8 |

8 |

0 |

|

Cambridge |

38 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

|

New Bedford |

38 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

|

Pittsfield |

37 |

8 |

8 |

0 |

|

Quincy |

36 |

8 |

0 |

8 |

|

TOTALS |

N/M[4] |

142 |

43 |

99 |

[1] See: https://mass-cannabis-control.com/documents/ filter documents by “Marijuana Establishment Data”

[2] The Commission does not disclose application numbers or event dates on its published reports. Therefore we calculated day counts by using the report dates.

[3] One application was denied and subsequently approved for a provisional license

[4] N/M Not Meaningful

MARIJUANA IN MASSACHUSETTS STUMBLES, READ MORE..

LANDLORDS CONTROL MASSACHUSETTS CANNABIS NOW.

OR...

OR..

MASSACHUSETTS MARIJUANA DELIVERIES, CLICK HERE.

OR..

MASSACHUSETTS MARIJUANA MARKET SIZE, READ THIS.

OR...

MASSACHUSETTS COMMUNITY HOST AGREEMENTS, WHY??