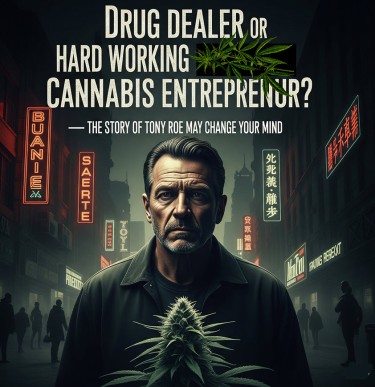

Drug Dealer or Hard Working Entrepreneur: The Dedication of Tony Roe

Meet Tony Roe, age 30, of Moatview Court, Priorswood, Dublin 17 - a man so dedicated to his craft that he literally conducted business during his own sentencing hearing. While most people would be sweating bullets, contemplating their life choices, or desperately trying to look remorseful for the judge, Tony was out here making moves. He smuggled alprazolam tablets worth €160 and some cannabis into Dublin's Criminal Courts of Justice building and successfully completed a transaction with another defendant right there in the courtroom.

Let's pause to appreciate the sheer audacity of this moment. Tony was sitting in Circuit Court, surrounded by guards, judges, lawyers, and bailiffs, waiting to hear how many years he'd be spending behind bars, and he decided this was the perfect time to expand his market share. That's not criminal behavior - that's entrepreneurial excellence. That's the kind of hustle mentality that would make Gary Vaynerchuk weep with admiration.

In any legal industry, Tony Roe would be celebrated as a sales legend. This is a man who identified an underserved market (court defendants), recognized a business opportunity (captive audience with high stress levels), developed a distribution strategy (courthouse smuggling), and executed flawlessly under pressure (literally during sentencing). He turned his own legal troubles into a business opportunity. That's not criminal thinking - that's consultant-level strategic planning.

But here's the cosmic joke that defines our entire drug policy framework: Tony Roe's only "crime" was engaging in consensual commerce with products that adults wanted to purchase. Strip away the legal framework, and you have one adult providing desired goods to another adult who voluntarily exchanged money for those goods. The "criminality" exists solely because a government - influenced by pharmaceutical companies and prohibition profiteers - decided that certain molecules are forbidden while others are mandatory.

If Tony had been selling alcohol in the courthouse cafeteria, he'd be a vendor. If he'd been selling prescription drugs with a pharmacy license, he'd be a healthcare provider. If he'd been selling tobacco products in the courthouse gift shop, he'd be a retailer. But because he was selling cannabis and alprazolam without government permission slips, he's a "criminal" with 124 prior convictions. The only difference is paperwork and political connections.

The Entrepreneurial Spirit vs. The Regulatory State

Tony Roe represents everything that's simultaneously right and wrong with how we think about drug commerce in the modern world. On one hand, he's clearly operating outside legal frameworks and has accumulated an impressive 124 prior convictions, including 29 for drug dealing. On the other hand, he's demonstrating exactly the kind of customer service dedication and market responsiveness that we celebrate in legitimate industries.

Consider the business acumen on display here. Tony identified that court defendants represent a high-anxiety customer base with limited access to stress-relief products. He recognized that courthouse security creates supply chain challenges but didn't let that deter him from serving his market. He developed creative logistics solutions (smuggling techniques) and maintained operational security even under direct judicial supervision. These are exactly the skills that make successful entrepreneurs in legal industries.

The alprazolam transaction is particularly telling from a market analysis perspective. Alprazolam (Xanax) is prescribed legally to millions of people for anxiety disorders, but courthouse defendants often don't have access to their medications while in custody. Tony identified this service gap and provided a market solution. In a rational system, this would be called "meeting customer needs." In our current system, it's called "drug dealing."

The cannabis component reveals another market inefficiency that Tony was addressing. Ireland's medical cannabis program is extremely limited, and recreational use remains illegal despite overwhelming evidence of safety and efficacy. Tony was essentially operating an unregulated dispensary for adults who prefer cannabis to alcohol for stress management. If this were happening in Colorado or California, he'd be a licensed retailer paying taxes and following regulations.

But let's address the elephant in the room: Tony's 124 prior convictions suggest he's not exactly a model citizen operating with perfect judgment. However, this criminal record is largely a product of the system that created the conditions for his entrepreneurship in the first place. When you criminalize consensual commerce, you create artificial scarcity that generates enormous profits for those willing to accept the legal risks.

The economics are straightforward: prohibition creates a risk premium that makes drug dealing far more profitable than most legitimate employment available to someone like Tony. If cannabis and alprazolam were legal and regulated, the profit margins would collapse to normal retail levels, eliminating the incentive for courthouse smuggling operations. Tony's entrepreneurial energy would likely be channeled into legal businesses with lower risk-reward ratios.

This highlights the fundamental flaw in prohibition logic: the system creates the problems it claims to solve. By criminalizing drug commerce, we ensure that only people willing to break laws will participate in drug commerce. Then we act shocked when drug dealers turn out to be people who break laws. It's like outlawing restaurants and then complaining that only criminals are feeding people.

The Philosophy of Consensual Crime

Tony Roe's courthouse caper forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about the nature of crime itself. If two adults voluntarily engage in commerce involving products that one wants and the other provides, where exactly is the victim? Who was harmed by Tony's transaction with another court defendant? The answer reveals the artificial nature of drug crime as a legal concept.

Traditional crimes have clear victims: theft harms property owners, assault harms physical persons, fraud harms financial victims. But drug commerce between consenting adults creates no identifiable victim other than the abstract concept of "public order" or "social welfare." The "crime" exists only because authorities declare it criminal, not because any individual person was directly harmed by the transaction.

This distinction matters enormously because it exposes drug prohibition as fundamentally different from other criminal law. When Tony sells cannabis to someone who wants cannabis, he's not violating anyone's rights or causing any harm that wouldn't exist if the transaction were legal. The "criminality" is entirely manufactured by legislative decree rather than emerging from inherent moral or practical concerns.

The courthouse setting makes this even more absurd. Both Tony and his customer were already in custody for other offenses, surrounded by armed guards, facing judicial proceedings. They weren't disrupting public order, endangering children, or threatening community safety. They were quietly completing a business transaction that would have been perfectly legal if conducted with different molecules or different paperwork.

Singapore's death penalty for drug trafficking illustrates how arbitrary these legal frameworks really are. The same act that results in execution in Singapore might result in a business license in Amsterdam. The moral weight of the behavior doesn't change - only the political jurisdiction. This geographic lottery of prohibition reveals that drug laws reflect political choices rather than universal moral principles.

The real crime in Tony's story isn't the drug transaction - it's the system that criminalizes consensual commerce while allowing pharmaceutical companies to legally distribute the same substances through captured regulatory processes. Alprazolam is perfectly legal when sold by licensed pharmacies at massive markups, but somehow becomes criminal when sold by Tony at market prices.

This double standard exposes prohibition as a protection racket for pharmaceutical monopolies rather than a public health measure. The same molecules are simultaneously medicine and poison depending on who's selling them and who's profiting from the transaction. Tony's crime wasn't harming people - it was competing with licensed monopolies without paying the required bribes (licensing fees).

System-Generated Criminality

Tony Roe's 124 prior convictions tell a story about how prohibition systems manufacture criminals rather than protecting public safety. When you criminalize widespread human behaviors like drug use, you don't eliminate those behaviors - you just ensure that everyone who engages in them becomes technically criminal.