Rearing Its Ugly Head Again: The Massachusetts Host Community Agreement

Silence can be Deafening: If a teacup falls off a shelf when no one is there to hear it, can the pieces be put back together?

After Cannabis Control Commission public meetings were closed by protesters in December & January, the Commission announced a January 23rd public listening session to hear the state’s Social Equity and Economic Empowerment applicant’s concerns and frustrations with the current application and licensing process. Two issues battled for first place; a lack of transparency in the application review process and challenges securing a coveted Host Community Agreement (HCA). The HCA is the first step in the licensing maze. No HCA, no license. No kidding.

Few issues have been as universally controversial in Massachusetts municipal government as the HCA. In a recent Forbes article that made the rounds two days prior to the public hearing, Kris Kane of 4Front Ventures[1], an integrated multi-state operator argued that the HCA process is “perhaps Massachusetts’ most fatal mistake” in the license approval scheme:

“The law purposefully made it difficult for towns to ban cannabis businesses, requiring a vote of the town’s residents in most cases. Yet the HCA requirement has served as a defacto ban, with towns simply refusing to grant them as a means to keep cannabis businesses out. When they are willing to grant HCAs, municipalities often go to the highest bidder, disadvantaging smaller and mom-and-pop startups.”

How we got here

The legislature granted the state’s 294 towns and 57 cities material control over the local marijuana approval decision-making process. Many communities, faced with the complex tasks of managing day to day municipal government, and lacking the regulatory knowledge of the state’s Cannabis Control Commission, looked at their past exposure to marijuana licensing; the state’s 2013 medical marijuana program.

In 2013, a pool of approximately 189 prospective applicants began a near 10-month marathon, led by the Department of Public Health (DPH), to complete the application process and secure a license. The process was complex and competitive, and license counts were limited to a minimum of one, and a maximum of five, per county, and only 35 statewide. Applications were required to “be hand-delivered on Thursday, November 21, 2013, to the [DPH], between the hours of 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m.” The DPH, like a college professor posting grades, issued all of its decisions on January 31, 2014[2], approving only 20 licenses.

Under the medical program, competition was limited, licenses were few, all applications were due on the same day, and it made sense under that scheme to secure a location as the initial step of the municipal approval process. Demanding a location before municipal approval under the unlimited and rolling recreational program makes far less sense. But without state guidance, most municipalities fell back on what they knew; the 2013 medical process – location first, municipal approval second.

Adverse consequences of driving by the rear-view mirror

“And now my friend, the first-a rule of Italian driving. (tossing rear-view mirror from vehicle) What's-a behind me is not important” The Gumball Rally (1976) Raul Julia

Under the current recreational program where the license count is unlimited (though municipalities may limit the number of marijuana retail outlets within their community), requiring a location first might be counterproductive by placing actual control in the hands of profit-seeking landlords versus citizen-focused community leaders.

In a typical community, once zoning is established and the number of HCAs are announced, a mad dash of real estate musical chairs begins. Aspiring licensees uncover every possible location, and landlords, realizing their signature is the gateway to a municipal application, often increase their price and demand non-refundable deposits to issue a letter of intent – that holy grail of a document needed to apply to the municipal governing body for an HCA.

Case in Point

The Town of Natick, as soon as it finalizes its bylaws, will likely be the last community to start accepting marijuana retail applications. Natick has eight Section 15 retail liquor licenses (alcohol sold to be consumed off-premise) which translates to two marijuana retail stores. Natick has zoned marijuana retail primarily to several pockets along the popular Rte. 9 retail corridor.

By mid-September 2018, 48 parties had approached the town’s Economic Development Director to express interest in a marijuana retail license. Aside from Boston, Cambridge, and Somerville, there are few sizeable communities that have not allocated most of their retail marijuana HCAs. There are likely far more than 48 parties interested in those two retail opportunities today. In the state’s Social Equity training program, 70 participants have indicated a desire to pursue a retail opportunity and that class will complete the program in April 2020.

Cruising Rte. 9 a trained eye can see where the marijuana stores might situate; Kid’s Room, a former children’s furniture store next to Ferguson Supply that has been mysteriously vacant for over ten months despite the Boca Raton-based property manager stating they have a tenant; Kid-to-Kid, a former pre-owned children’s clothing store that closed a couple months after its neighbor, and too, has been uncharacteristically vacant. Or the still vacant Papa Gino’s that closed in February 2019[4]. The broker for the Papa Gino’s property disclosed last March that while the building was likely worth $1.1 million, the owner knew it was in the tightly zoned marijuana overlay district and was asking $1.5 million without contingencies for receiving local or state license approval); a 38% premium over the property’s market value.

Should Natick require applicants first secure a location, it will be the landlords that have chosen the finalists; candidates with deep pockets that can pay the highest rent and year-long carrying fees to keep other candidates out of the prospective applicant pool. The state’s Social Equity and Economic Empowerment applicants will be locked out of the Natick application process before it even begins – one of the resounding complaints at the January 23rd listening session. But this time, it just might play out in real time, in front of everyone’s eyes.

Like many communities, Natick has been touched by substance abuse. Each August, the First Congregational Church in downtown Natick hosts a sea of purple flags – this year 2,033[5] – to commemorate and remind residents of the lives lost in Massachusetts to opioid abuse[6]. The Health Department leads Natick 180 which brings various organizational leaders together to create community solutions around prevention and treatment strategies (I quietly left a recent meeting holding back tears after a screening of the Chris Herren movie, “The First Day”). If only a handful of well-healed applicants can make it past the landlord test, the Natick Select Board will be deprived of considering applicants that might be more community-focused, more situationally aware, and an overall better fit for the community, but ultimately not as profitable a tenant for the landlords.

Simple economic theory of supply and demand dictates that when 48 candidates descend upon six or so landlords, prices will increase – dramatically, and smaller operators will be priced out of the market. Should communities in this situation first screen the applicants (as one western Massachusetts city is now considering) before site selection, and then award an HCA, supply and demand come into balance. In the case of Natick, two applicants approved by the Town could select a location without the frantic pressure of a competitor desperate to lock up space to stay in the licensing game. Rents will reflect the local market, and not the typical panic pricing associated with retail marijuana space.

Empty storefronts don’t employ people and those people don’t buy coffee.

Empty storefronts aren’t good for a community. Empty storefronts don’t employ staff; there’s no one to purchase coffee, gas, lunch, or snacks from local merchants. When multiple storefronts come off the market while they await a local licensing decision but only two stores are approved, the other merchants who sought space during the hold time likely went elsewhere – not good for the host community. Landlords collect rent or hold fees but the local municipality doesn’t collect taxes from an empty business and local residents don’t find jobs. In Natick, this impact is likely limited. There are only two HCAs to be awarded and few prospective locations. Overlay this situation onto communities like Boston and Cambridge where zoning is far wider and many more HCAs are in play, and the lock-it-up-and-hold-em strategy can have an adverse impact.

Landlords are often controlling the process, and laughing all the way to the bank.

Landlord’s can’t be blamed. They are doing what they should do; maximizing the income value of their asset. In some instances they are being granted absolute control.

The Town of Webster is a prime example, sitting on the Connecticut border and known for music venue Indian Ranch and lake Chaubunagungamaug, Massachusetts’ third-largest water mass. Webster has two personalities; inexpensive real estate and a typical household income about 2/3rds the statewide median (when a nephew couldn’t find a financially-suitable 3-family in red-hot Worcester, he found an affordable fixer-upper in Webster), and million-dollar lake homes. Webster is also home to Webster Bank and Mapfre Insurance. Before we advance further, let’s take a short detour from Webster.

Visiting the Berkshires

Theory Wellness is a marijuana store in Great Barrington, a quiet western Massachusetts town, just eight miles from the New York state border. The shop opened in 2017 as a medical marijuana dispensary and according to CEO Brandon Pollock, still serves about 1,000 regular medical customers. As a recreational store, Pollock reports[7] that approximately half of their more than 50,000 customers travel over the New York border, a fact not lost on New York state legislators eager to legalize recreational marijuana and keep the tax revenue in their home state. Great Barrington’s challenge is determining how to use the influx of marijuana tax proceeds; $1 million in the first six months of operations and almost $775,000 from July through September 2019.

Back to Webster

Webster shares a border with Connecticut (which, like New York, still hasn’t legalized recreational marijuana) and hosts a 4-mile stretch of I-395 that provides direct access from Connecticut. The town is trying to find ways to revitalize its downtown area, create more foot traffic, bring in more visitors, and improve its local economy. Last year, town officials toured downtown Hudson to learn how Hudson staged a remarkable revival of its downtown area.

Despite a direct roadway to collect tax revenue from Connecticut customers, the town sought to ban retail marijuana but ultimately allowed two retail stores (the minimum) when voters rebuked the ban. Despite empty buildings and ample available space in several plazas, zoning was set for a sleepy retail complex known as Webster Plaza, and the Webster Industrial Park.

Webster Plaza is an approximate 260,000 SF ailing retail center near the Oxford town line. The left side of the plaza is nearly dark (dark is apparently industry lingo for when the tenant moves out and shuts off the lights – for good, as Shaw’s did in 2014). Next to the former Shaw’s are former Olympia Sports, Radio Shack, and GNC. GNC relocated to a more upbeat location in Webster. What remains is a nail salon, coin-op laundry, and a beauty supply shop. The right side of the plaza was anchored by a K-Mart (now dark). Aubuchon Hardware store, Rent-A-Center, and Dollar Tree each moved down the street to livelier locations, leaving Dollar Tree as the remaining brand name retailer. The plaza is owned by a private real estate firm in Long Island meaning that all conventional marijuana-zoned retail is owned by a single landlord.

Space in the plaza was advertised at $14 to $17 per foot but prospective marijuana applicants were advised to bid at least $25 to be considered. The town entertained two applicants for HCAs, one of whom had been assured they could apply without first securing a location. After a review process, the town announced it was “impressed that both retailers had the abilities to operate a safe and successful marijuana retail store in Webster.” The town then “informed the leasing agent that both retailers had completed and passed [the town’s] review process and [the town] would enter into a host agreement with whomever [the leasing agent] wished to lease to.” The leasing agent selected the high bidder. Aside from owning the one retail location approved for retail marijuana, the owner’s leasing agent now enjoyed control of the final decision.

The alternative was the local industrial park. The town suggested a local marine dealership located at the entrance to the industrial park, contact the applicant. The marine store was downsizing and the owners planned to erect a demising wall to separate the space they no longer needed. Space in the industrial park is advertised at $8.50 a foot; the marine store wanted $27 a foot and a $15,000 non-refundable deposit. At $8.50 a foot, space includes heat, air conditioning, and a doorway. The marine store required the new tenant to install their own heat, AC, and a doorway as there was no exit from the space once the demising wall went up. When the applicant balked, the marine store wisely held firm. The property was leased to another marijuana applicant eager to secure the final HCA within ten days.

The twice-loser reminded the town they had agreed the applicant could apply without a location. In October, the town acknowledged and agreed to refund the $500 application fee. At last count it has been nearly four months and no check.

Twenty minutes north, in Worcester, mother and son team Jennifer and Louis Gaskin were seeking a location for a cannabis cultivation business. Louis is a Social Equity candidate. They found a warehouse and paid the owner a $5,000 deposit to take the property off the market. Gaskin paid an additional $12,000 toward the first and last month’s rent but when they sought the landlord’s cooperation to apply for the HCA, the landlord demanded $100,000 to fund property renovations as a condition of assisting. “That’s where the conversations broke down,” Gaskin said. Gaskin later learned another individual had approached the landlord claiming to have $2.4 million in the bank. The landlord dropped the Gaskins, but kept their money.

When landlords control the process, the competitive landscape shifts from what’s good for the community to what’s best for the landlord. Small teams can’t compete.

The Town of Maynard

The Town of Maynard wrestled with the issue of what comes first; the location or the HCA for six weeks during late summer 2019. After vetting an applicant and establishing comfort with their financial and operational viability, Maynard approved the operator, granted an HCA, and allowed them six months to find a location. It was a unique approach brought on, in part, by town counsel’s willingness to consider the social implications of flipping the process around but retaining location control with the town. The applicant cannot apply for a special use permit until the applicant’s location is approved by the Select Board. If a location isn’t identified in six months, barring an extension, the HCA expires. This bifurcated approach allowed the Board to consider all applicants and select the best operator for the town.

Collateral consequences

When Maynard granted their bifurcated HCA and announced they would wait to see how the currently approved operators performed before considering additional retail HCAs, the competing retail applicants left town and something interesting happened to real estate prices. A building owner had bought a property for $320K in February 2018. Just 18 months later, in August 2019, the owner declined a $500K offer from competing marijuana operators. When the frantic marijuana rush left town, the owner reduced the asking price to $449K and then to $399K before coming under agreement. Another landlord who was thick with prospective marijuana retailers quickly found his premium rates were no longer gaining interest with conventional renters. Deflating the marijuana bubble helps fuel non-marijuana activity..

Putting the teacup back together before the clock runs out

The current dilemma for Social Equity and Economic Empowerment applicants is timing. Massachusetts will ultimately only host a certain number of marijuana retail stores. Ask five informed people on what that final number will be, and you will likely walk away with at least seven concrete answers. While no one can know for certain, some factors are known.

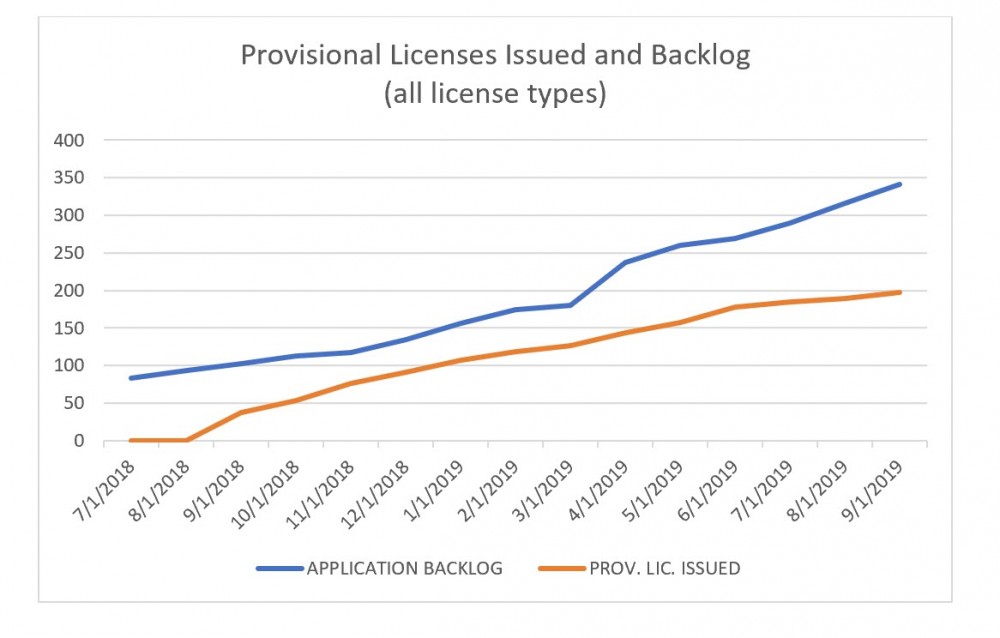

As of January 17, 2020, there are 35 stores open and operating. Trailing closely behind them five stores with a final license, 11 are getting ready for a certificate to commence operations. Next in line, 75 stores with a provisional license are preparing for the inspections that will lead to a final license. At the back of the line, 169 applicants anxiously awaiting an answer or an RFI (request for additional information) from commission staff. Eventually, all of these stores will clear their hurdles and open and there will be 284 retail outlets. Add in communities like Boston (with only 8 applications in the queue but with 55 retail HCAs available), Cambridge with no applications in the queue and at least 9 retail HCAs available) and Somerville (only one application in the queue with six HCAs available), and there should be an additional 60-something stores. Massachusetts has numerous communities that might allow retail stores, but don’t have a large enough population count to support one (98 towns allow retail marijuana but have fewer than 5,000 people each). Time to find suitable host communities with retail availability is slowly slipping away for Social Equity and Economic Empowerment applicants.

The Cannabis Control Commission proposed an additional guidance memo for municipalities that addresses host community agreements. The focus of that guidance is to quash the excessive fees many communities are extracting from marijuana license applicants that exceed the state limited three percent community impact fee. The guidance is loudly silent as to alerting municipalities that they have the power to approve applicants first, and locations second – the so-called Maynard approach. This is the lynchpin issue that could get many of the frustrated Social Equity and Economic Empowerment applicants into the competition for a municipal HCA.

The commission may eventually respond to the HCA frustrations expressed on January 23rd. Hopefully, it will be before the final HCAs have been awarded. Attorneys like to say that justice delayed is justice denied. Solving a problem when the solution becomes moot, is no solution at all. Social Equity and Economic Empowerment applicants will require a fair shot at HCAs if they’re to assemble the pieces of a license application before it’s too late. Hopefully their voices didn’t fall on deaf ears.

Have you had an adverse experience with landlords or municipalities (or some other party playing slight of hand games)? Connect with me and let me know. David@NewCannGroup.com

David Rabinovitz

[2] https://www.metrowestdailynews.com/article/20140131/NEWS/140139161/11553

[5] https://www.wcvb.com/article/sea-of-purple-flags-honor-victims-of-opioid-crisis/28820377

[6] Fair Disclosure – I don’t like those flags but am glad they are there. This Massachusetts tradition was started by Kathy Leonard (Testa) in honor of her son, Jonathan, a talented baseball player and musician. His dad, Ed Testa, and I were business partners for many years. I have a picture of our kids together during a 1998 trip to Disney. Jonathan died from an overdose on December 17, 2014.

DAVID RABINOVITZ ON MASSACHUSETTS MARIJUANA, READ MORE..

MARIJUANA LICENSING IN MASSACHUETTS, READ THIS FIRST.

OR..

HOW BIG WITH THE MASSACHUSETTS MARIJUANA MARKET GET?