Much has been written about Sean Combs’ acquisition of multi-state vertically integrated cannabis assets.

Per Wikipedia: “In finance, the greater fool theory suggests that one can sometimes make money through the purchase of overvalued assets — items with a purchase price drastically exceeding the intrinsic value — if those assets can later be resold at an even higher price. In this context, one "fool" might pay for an overpriced asset, hoping that he can sell it to an even "greater fool" and make a profit. This only works as long as there are enough new "greater fools" willing to pay higher and higher prices for the asset. Eventually, investors can no longer deny that the price is out of touch with reality, at which point a sell-off can cause the price to drop significantly until it is closer to its fair value, which in some cases could be zero.”

Numerous industry pundits have weighed in on whether the deal was good and if so, for whom. When contacted by Cannabis.net, I commented that based upon Massachusetts asset values and current market conditions, it seems like he may have overpaid, but one will never know without seeing all the financial and other due diligence data. But this isn’t a story about Mr. Combs or his deal. It’s about the other deal discussed in the Cannabis.net article.

Cannabis assets are in some way, like a block of ice on a hot August sidewalk. They are melting in value, not from the sun but from the shortened timeline until interstate commerce takes effect. We don’t know the date, but we do know it is sooner than it was a couple years ago. When that day comes, as I opined in April, cultivation asset values will enter a free fall. As I started to dig into the topic of the fragility of cannabis cultivation asset values, I was also hosting The Green Rush, a 2-hour weekly cannabis talk show. On the November 5, 2021, episode, we took a deep dive into interstate commerce with Professor Robert Mikos of Vanderbilt Law and we were joined by several guests, including Beau Whitney, a pretty smart economist who tracks cannabis and has estimated that the capital destruction resulting from legal interstate transport of cannabis will approach $80 Billion. That was a year ago. More indoor cultivation assets have come online (including a $20 million cultivation facility in western Massachusetts back in September 2022) and with inflation, those newly minted assets cost more, so $80B might be a bit light.

In Massachusetts stores are being given away for free in highly limited instances. Don’t all rush out here. We have about 235 stores open and the free give aways are all unique circumstances and there are only a handful. This story is about the most prominent one, Pleasantrees. Aside from an industry-wide email blast (kudos to whoever curated that list), a notable comment in a Cannabis.net article, and an article in the Green Market Report, their Lease Takeover Opportunity “offering a no cost acquisition of its assets” discloses some interesting data.

The Amherst, Massachusetts store opened in August 2021 and is situated directly adjacent to University of Massachusetts (main campus) and is in close proximity to Amherst College. The store is in the former site of Rafters Sports Bar & Restaurant, the go-to dive bar for local college students. The local non-student population is 40,000 and there are over 31,000 students in attendance within one mile (quoted data is from the Pleasantrees flyer). Bear in mind that not all college students are 21 years of age, the legal age to purchase regulated marijuana in Massachusetts.

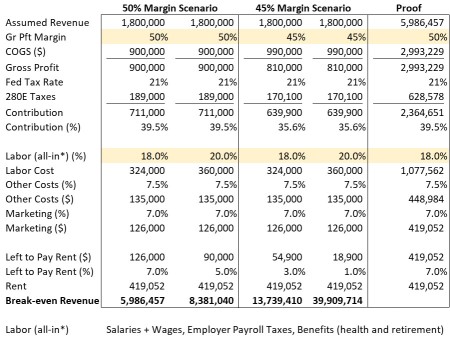

The store is reported to generate $100K to $150K per month in revenue. Let’s be generous and assume the higher end. This is a $1.8MM annual revenue store.

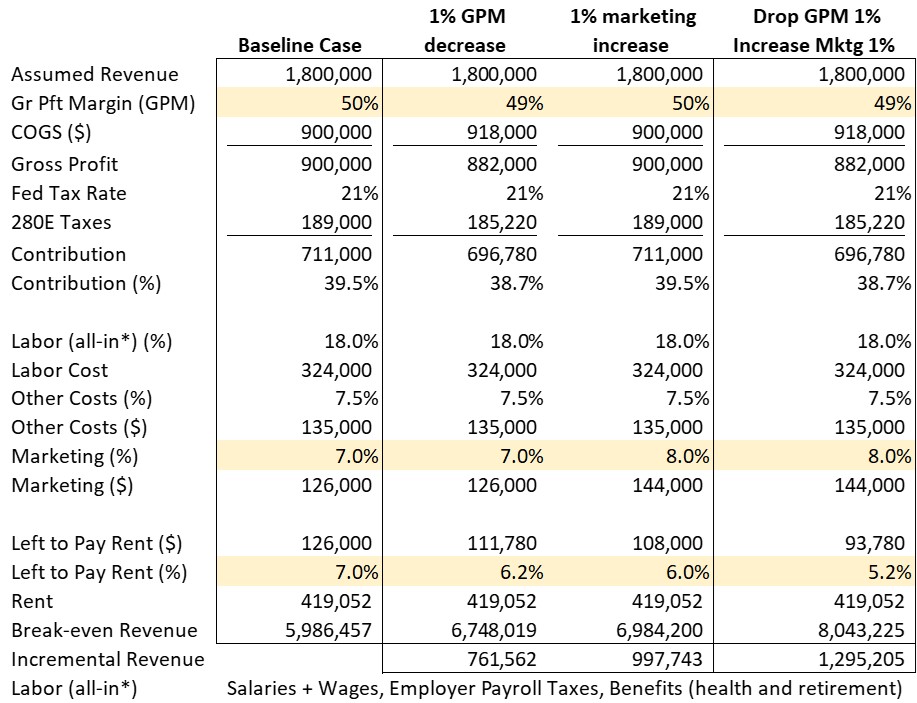

Massachusetts has 351 municipalities, ranging from Gosnold in Dukes County (Martha’s Vineyard) with 77 residents to the City of Boston with 667,137 residents. Of those 351 communities, only 14 have populations exceeding 70,000. So, Amherst is looking like a great location. Let’s dive into a back-of-the-envelope analysis of a few scenarios for the Amherst store. We break this down step by step for those who are not as comfortable with figures.

-

As to retail stores, let’s assume cost of goods sold (COGS) at about 50% of sales (I have seen costs as high as 55% but not much lower than 50%) – that’s $900K of COGS leaving a gross profit of $900K. Gross profit margin (GPM) is equal to 100% minus COGS.

-

Cannabis retailers pay taxes on gross profit pursuant to Internal Revenue code section 280E. The current federal corporate tax rate is 21%, so federal income taxes are estimated at $189,000, leaving a $711,000 contribution to overhead costs.

-

I reached out to a few friendly and successful independent Massachusetts retailers. From what I have heard, labor costs for cannabis retailers runs around 18% to 22% of sales (I have only asked a few dispensary owners, so the data points are limited). Struggling stores have labor costs in the mid to upper 20% range. That pegs labor at $324K to $360K. I have seen higher labor costs (as a percent of sales), but that is when the store is still ramping up. If you’re an operator and can contribute to my knowledge, reach out, my contact information is listed below.

-

Let’s assume all other costs (other than rent and marketing) are only 7.5% of revenue – POS systems, security, utilities, store supplies, license renewals, training, general expenses, etc. 7.5% might be light, but our goal is to get a good sense of the opportunity economics.

-

Marketing and promotion seem to be highly guarded numbers, but one successful operator shared that they allocate about 7% of sales to “general advertising” costs. Someone else suggested 3.5%. I went heavy on the marketing investment to drive sales.

Deducting the above costs from revenue leads to how much money is left to pay rent. The monthly rent of $34,921 equates to about $420K annually. If we divide the rent amount by the percentage left to pay rent, the result is the break-even level of revenue needed to pay the bills and have zero profit. That is the first step of what we’re looking for.

At an 18% labor cost, this store needs to increase sales to nearly $6 million to break even. At a 20% labor cost, the break-even jumps to nearly $8.4 million. If the gross profit margin drops to 45%, those break-even figures jump even higher. Massachusetts is experiencing margin compression and the Massachusetts cannabis market is under great stress as Zach Huffman pointed out in a feature article in the November 9, 2022, Grown In newsletter; “A wave of debt restructurings threatens Massachusetts’ adult use market.” (Kudos to Zach Huffman’s reporting on this issue and his cost per gram research – if you don’t subscribe, you should). Our 50% margin figure might be generous in the current environment.

Ever see two gas stations within sight of one another yet one has a price per gallon up to ten cents higher than the competitor, yet there are still customers buying from the higher priced station? Gas, like ag products, is a commodity item. So why will customers pay a bit more; because the station is the one the customer is accustomed to. People are creatures of habit and once a habit forms it can take an effort to dislodge. Customers instinctively visit certain stores for certain products. They become accustomed to the routine, the location, parking, layout, products, menu boards, etc. The customer knows what to expect and they are comfortable with that expectation. Breaking that habit as an outsider can be challenging. Just ask the owner selling the cheaper gas why customers still visit the other station that charges 10 cents more a gallon. Habits are hard to break.

Amherst has 3 retail cannabis stores. The first opened for adult-use in September 2020 and also serves medical patients. The second opened for adult-use in August 2021. Pleasantrees opened for adult-use in February 2022 (medical opened earlier which is likely why the company states the store has been open over one year).

To lure away a competitor’s clients will require discounted pricing, heavy marketing or both – and that costs money. Let’s look at how much from a revenue angle.

We went back to our data set and posed two questions. Assuming a 50% gross profit margin, what is the impact of dropping our profit margin by 1%? Under the same 50% gross profit scenario, what is the impact of increasing costs for marketing by 1%? We had to treat these questions differently because of the 280E impact. A decreased gross profit margin decreases federal taxes under 280E but an increase in marketing costs does not as marketing is not 280E deductible.

Consider this:

-

Every one-percent drop in the gross profit margin translates to an additional $760K in revenue to break even. Drop prices by 5% and break even increases by $3.8 million for a store that appears to be operating at a loss and is only generating $1.8 million of annual revenue at present.

-

For every 1% Increase in marketing, revenues must increase by about $1 million to break even.

-

Drop prices by 1% and increase marketing by 1% and sales must rise by $1.3 million to break even.

This is not a game for the faint of heart. If strong discounts are needed to drive volume, $8MM might not be enough to cover costs, never mind generate a profit. If you want a free store, you better come with a lot of free cash to fund the turnaround. Someone will agree to assume these stores. The open question is how long it will take and at what cost. For their sake, let’s hope they have good financial advisors.

Before he does his next deal, does anyone know if Mr. Combs is hiring?

Comments? Hit me up. DavidR@CannaVentureLabs.com or drabinovitz@gmail.com. Text me at 617-281-0710.

Coming soon

Run for the Hills: Will the Massachusetts market crash in Feb. 2023 and why that date is in my crystal ball

Follow me on LinkedIn, David Rabinovitz, here!