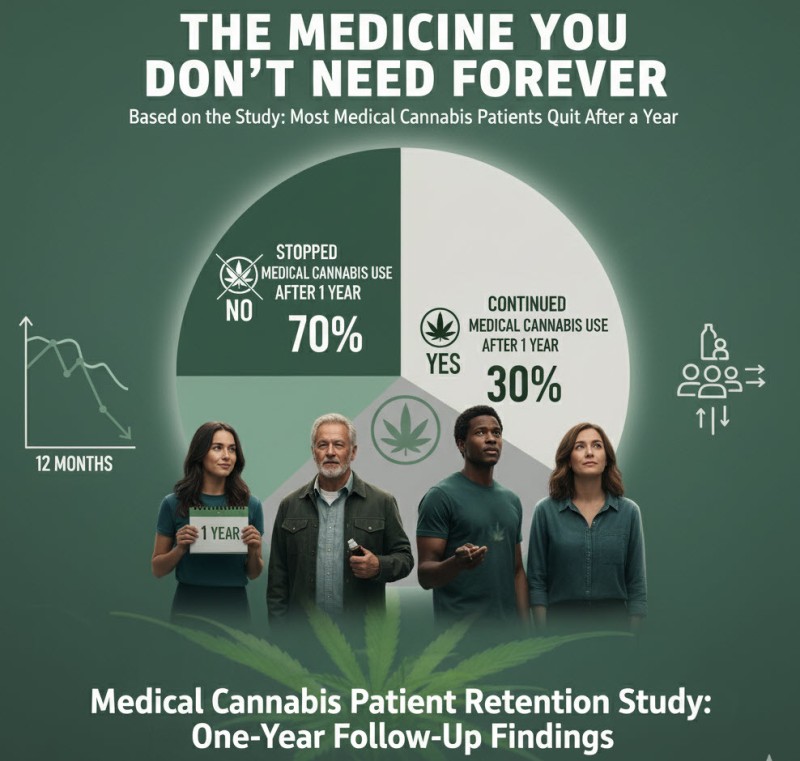

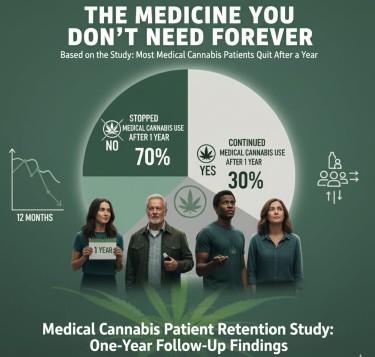

A fascinating study out of Pennsylvania just delivered news that should terrify pharmaceutical executives and delight anyone who understands what real medicine looks like. According to research published in PLOS One, 58% of medical cannabis patients quit using it within a year, with nearly half stopping within just three months.

Before prohibitionists start celebrating, let's put this in perspective. When patients stop using medical cannabis, it's typically because they no longer need it – not because they can't stop using it. This stands in stark contrast to opioids, where patients often continue using long after their original pain has resolved, trapped in a cycle of dependence that pharmaceutical companies designed and profited from.

The Pennsylvania study tracked 78 chronic pain patients for two years, revealing discontinuation patterns that would be impossible with truly addictive substances. Patients simply stopped when the treatment no longer served their needs. No withdrawal clinics, no tapering schedules, no life-destroying addiction spirals – just rational medical decisions based on personal experience.

This research inadvertently exposes the fundamental lie underlying cannabis prohibition. We've been told for decades that marijuana is dangerously addictive, a gateway drug that destroys lives. Yet when people use it medically, they walk away when they're done, like finishing a course of antibiotics.

Compare this to the opioid crisis, where pharmaceutical companies deliberately engineered addiction. Purdue Pharma's internal documents revealed they knew OxyContin was highly addictive while marketing it as having low abuse potential. The result? Over 500,000 overdose deaths and counting, with many patients unable to stop even when their original pain resolved.

The study found that older patients were more likely to discontinue cannabis treatment, with an average age of 72 compared to 65 for those who continued. This suggests that conventional medical training's skepticism toward cannabis might actually be working against patient welfare.

What emerges from this research isn't a failure of cannabis medicine, but proof of its fundamental safety. Here's a substance that provides therapeutic benefit without creating the dependency that characterizes truly dangerous drugs. No wonder it remains federally illegal – a medicine you can grow yourself and easily discontinue threatens an entire industry built on perpetual treatment.

The Opioid Comparison: When Medicine Becomes Bondage

To understand why cannabis patients can simply walk away from their medicine, we need to examine what happens when they can't. The opioid epidemic provides the perfect counterexample – a case study in what pharmaceutical addiction looks like when engineered for profit.

Between 1999 and 2021, over 500,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, with prescription opioids playing a central role. Unlike the cannabis patients in Pennsylvania who stopped treatment when it no longer served them, opioid patients often find themselves trapped long after their original pain has resolved. Studies show that patients prescribed opioids for more than three days have a 20% chance of still using them a year later, even for minor procedures.

This isn't accidental. Internal Purdue Pharma documents revealed the company knew OxyContin was highly addictive while marketing it as having "low abuse potential." They deliberately targeted doctors who prescribed high doses, encouraged longer treatment periods, and downplayed addiction risks. The result was a generation of patients who started with legitimate pain and ended up dependent on substances that hijacked their brain chemistry.

The difference lies in the mechanism of action. Opioids create physical dependence by altering the brain's reward system and pain perception pathways. Discontinuation triggers genuine withdrawal symptoms – nausea, sweating, anxiety, and intense cravings that can last weeks. Cannabis, conversely, doesn't create the same neurochemical dependence. While heavy users may experience mild withdrawal symptoms, they're comparable to stopping caffeine rather than opioids.

The Pennsylvania study's discontinuation rates would be impossible with opioids. When 45% of patients stop using a medicine within three months, that's not addiction – that's rational healthcare decision-making. Patients use cannabis while they need it, then move on when they don't. This pattern is consistent with therapeutic use rather than dependency.

Consider the financial implications. The opioid epidemic generates perpetual customers – patients who remain dependent long after their original condition resolves. Cannabis creates temporary patients who use the medicine as needed, then discontinue treatment. From a pharmaceutical profit perspective, cannabis is a terrible business model because it actually works as medicine rather than addiction maintenance.

The age factor in the study – older patients being more likely to discontinue – reveals another crucial difference. Older adults, often more conservative about drug use, feel comfortable stopping cannabis treatment. This suggests the absence of the compelling physical dependence that characterizes opioid addiction. When 72-year-olds can casually discontinue a medicine, that medicine isn't creating bondage.

The opioid crisis killed more Americans than the Vietnam War while generating billions in pharmaceutical profits. Companies paid fines worth billions yet continued operating, treating overdose deaths as acceptable business expenses. The contrast with cannabis – where patients simply stop using it when they feel better – couldn't be starker.

This research inadvertently proves what prohibition advocates refuse to acknowledge: cannabis is fundamentally different from truly addictive substances. It's medicine that serves patients rather than enslaving them.

The Soft Drug Reality: Why Walking Away is Easy

The Pennsylvania study inadvertently confirmed what cannabis users have known for decades: marijuana is what drug policy experts call a "soft drug" – a substance that doesn't create the physical dependence or compulsive use patterns associated with truly problematic substances.

When 58% of patients can discontinue medical cannabis within a year, we're witnessing something that simply doesn't happen with genuinely addictive drugs. Imagine a study showing that 58% of cocaine users or 45% of heroin users simply stopped within three months because they felt better. It's absurd because those substances create neurochemical changes that make discontinuation extremely difficult.

Cannabis dependence, when it occurs, manifests more like caffeine dependency than opioid addiction. Heavy users might experience irritability, sleep disturbance, or decreased appetite when stopping, but these symptoms are mild and temporary. The cannabis patients in Pennsylvania didn't require medical supervision, tapering protocols, or addiction treatment – they simply decided the medicine no longer served their needs and stopped using it.

This reality terrifies prohibition advocates because it undermines their entire narrative. For decades, we've been told that marijuana is a dangerous drug requiring criminal penalties to protect society. Yet when people use it medically, they treat it like any other therapeutic intervention – useful while needed, discarded when not.

The study's finding that pain location didn't predict discontinuation rates is particularly significant. Whether patients had back pain, joint pain, or muscle pain, they were equally likely to stop using cannabis when their condition improved. This suggests that patients were using cannabis therapeutically rather than recreationally – seeking specific medical outcomes rather than intoxication.

The age differential provides additional insight into cannabis's soft drug nature. Older patients, typically more cautious about drug use and more concerned about dependency, were more likely to discontinue treatment. This pattern wouldn't exist with truly addictive substances, where age often correlates with longer dependence due to accumulated tolerance and physical adaptation.

Compare this to alcohol, which kills 140,000 Americans annually and creates physical dependence in about 10-15% of users. Yet alcohol remains legal and socially acceptable while cannabis faces federal prohibition. The cognitive dissonance is staggering when viewed through the lens of actual harm reduction.

The study's limitations – no data on specific products or functional improvements – actually strengthen its core finding. Without measuring therapeutic outcomes, researchers still observed that most patients voluntarily discontinued treatment. This suggests the decision wasn't based on ineffectiveness but on resolved need.

Cannabis's soft drug characteristics explain why cultivation remains federally illegal. A medicine you can grow in your backyard, use as needed, and discontinue without medical supervision threatens an entire pharmaceutical model based on perpetual treatment. When patients can walk away from their medicine whenever they choose, that medicine isn't creating the dependency that generates long-term profits.

The Pennsylvania study accidentally proved what should be obvious: cannabis is medicine, not addiction maintenance. Its soft drug nature makes it ideal for therapeutic use while posing minimal dependency risks.

The Medicine Big Pharma Fears: Grow Your Own, Use What You Need

The Pennsylvania study reveals why cannabis remains federally illegal despite overwhelming evidence of its medical benefits. It's not because marijuana is dangerous – it's because it's the opposite of what pharmaceutical companies want in a medicine.

Cannabis patients don't become permanent customers. They use what they need, when they need it, then move on with their lives. No monthly prescriptions, no dependency management, no perpetual treatment protocols. From a business perspective, cannabis is a terrible pharmaceutical product because it actually solves problems instead of managing them indefinitely.

The fact that you can grow cannabis in your backyard makes it even more threatening to established medical industries. Imagine if patients could cultivate their own blood pressure medication or grow their own antidepressants. The entire pharmaceutical model depends on scarcity and dependency – two things cannabis fundamentally undermines.

The study's high discontinuation rates aren't a failure of medical cannabis; they're proof of its success as actual medicine. When people get better and stop needing treatment, that's how medicine is supposed to work. The opioid epidemic taught us what happens when medicine is designed to create permanent patients rather than temporary relief.

Despite decades of prohibition propaganda, cannabis remains what it's always been: a soft drug with genuine therapeutic benefits and minimal dependency risks. The Pennsylvania research accidentally proved that marijuana is medicine you can walk away from – exactly the kind of medicine that threatens an industry built on perpetual treatment.

No wonder it's still illegal.